Broken Endodontic Files: Causes, Implications, and Retrieval Strategies

Understanding Reasons Behind Broken Endodontic Files

Fracture of a rotary file (NiTi or stainless-steel instrument) is a distressing yet not uncommon complication. Most separations occur due to cyclic (flexural) fatigue and torsional overload (3). In curved canals, repeated bending causes micro-cracks that accumulate (cyclic fatigue), and if a file’s tip binds while the motor keeps turning, torsional stress quickly snaps it (3). Other factors include complex file geometry (large taper, variable cross-sections) and manufacturing defects (3). Even brand-new NiTi files can break without warning, so many clinicians recommend single-use to limit fatigue (3). Modern martensitic/heat-treated NiTi files are more flexible (better fatigue resistance) (3), but this can trade off torsional strength. Common causes of file fracture include overloading an undersized canal, insufficient glide path, or metal wear from repeated use (3).

- Cyclic fatigue: Repeated flexing in curved canals creates stress points that eventually crack an NiTi file (3).

- Torsional stress: If the tip jams (e.g., against the canal wall) and the motor turns, torque overload will shear the file (3).

- Instrument design & misuse: Aggressive tapers, off-center cross-sections, or applying excessive force can predispose any endodontic file to fracture (3).

- Manufacturing/use factors: NiTi instruments may have microscopic defects; repeated sterilization or reuse accumulates micro-fractures even if no visible wear is seen (3).

How Often Do Files Separate? (Incidence)

Evidence-based studies show that instrument separation is relatively rare but not negligible. Reported incidence ranges from ~0.4% up to about 6% of treated canals (3). For example, a large specialist practice found separated files in about 3.3% of cases (1). NiTi rotary files tend to separate more often than stainless steel. One review noted ~2.4% separation for NiTi rotary systems (versus ~1% for reciprocating systems) (3). Using each NiTi instrument only once further drops the breakage risk (to ~0.9%) (3). Separation is most likely in curved molar canals (especially mesial roots of lower molars and apical thirds) (3). In short, while most treatments avoid this mishap, endodontists should expect a broken file roughly 1–6 times per 100 cases based on the evidence (3).

Clinical Implications of a Broken File

When an endo file fractures in the canal, it creates a metallic blockage. This can prevent effective irrigation and cleaning beyond the fragment, potentially harboring bacteria. However, a broken file itself is not toxic or inherently infectious (3). Studies show healing rates remain high (≈90%) even with retained fragments if infection is controlled (1). The location and stage of treatment at the break are key:

- Apical fragments: If a small file piece breaks in the apical third after adequate shaping, many clinicians leave it in place. They simply adapt the working length to the fragment, irrigate vigorously (e.g. NaOCl agitation), and fill to the instrument (1). Following up radiographically is essential. Success has been documented with this approach as long as the rest of the canal is disinfected (1).

- Middle/root fragments: A fragment lodged in the mid-canal often prompts an attempt to bypass or remove it. If a hand file can negotiate alongside the fragment, the canal can be fully instrumented to size and filled (often after placing a calcium hydroxide medicament to aid disinfection) (1). If bypass fails, obturating up to the fragment and long-term monitoring (with possible apical surgery later) is the fallback (1).

- Coronal fragments: When a file breaks in the coronal third, removal is usually attempted immediately, since the fragment is accessible. Techniques (see below) are used to retrieve it with minimal loss of dentin (1).

Clinicians must weigh benefits vs. risks. Attempting to remove a fragment often means cutting away dentin, which can weaken the tooth. Aggressive trephination risks perforation or strip perforation and can predispose the root to vertical fracture (3). Therefore, the dictum is “not harm”: if retrieval would compromise the tooth, obturating to the fragment is prudent (1). Infected cases or persistent lesions may eventually require surgery or extraction, but many teeth with separated files remain asymptomatic for years (1).

Techniques for Retrieving Broken Files

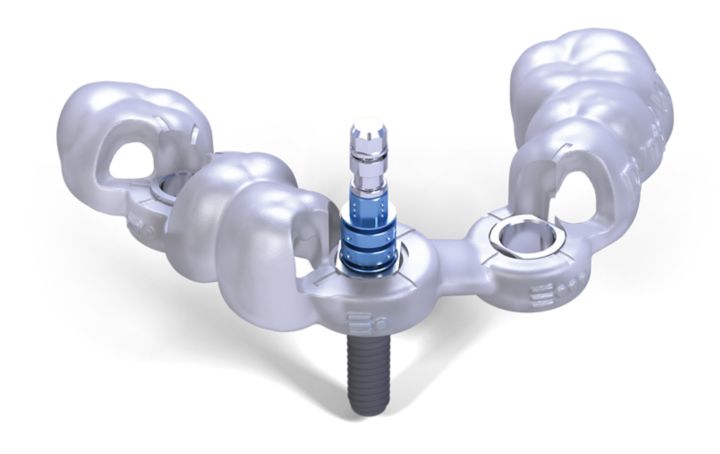

Modern endodontics offers many tools to deal with a broken file when removal is indicated. Key elements are a dental operating microscope (DOM) and fine ultrasonic instruments (3). Under high magnification, the clinician uses small ultrasonic tips (e.g. ET-20, ET-40) to carefully probe around the coronal end of the fragment and loosen it (3).

Specialized extraction kits exist. For example, the Masserann kit uses color-coded trephine drills to cut a trough around the fragment and a hollow tube with a plunger to grip it (4). Masserann is especially useful for large metal objects in straighter canals; success rates around 55% have been reported (4). Other systems like the Endo-Extractor or micro-forceps/loops (e.g., Ruddle’s extractor, Micro Rette) can grab exposed fragments. These work best when some part of the file projects coronally (4).

For small or apically located fragments, microtube-and-adhesive methods are powerful. This involves sliding a thin metal tube (often a hypodermic needle or custom microtube) over the fragment’s tip and using a tiny drop of cyanoacrylate or resin cement to bond the file to the tube (4). After allowing the adhesive to set (usually a few minutes), the tube is carefully withdrawn, pulling the fragment out with it (4). Variants include the “tube-and-wire” (lasso) and “tube-and-internal shaft” techniques (4). These adhesive methods can achieve success rates around 75–80% when ultrasonic alone fails.

Other important technologies include:

- Operating microscope (DOM): Often quoted as, “If you can see it, you can retrieve it” (2). Magnification and illumination make ultrasonics and forceps far more effective.

- Cone-beam CT: Pre-procedure CBCT imaging helps locate a broken file in 3D and choose the safest access route.

- Future/Advanced methods: Research is exploring laser and electrochemical (EDM) removal, but these are not yet standard in clinical practice.

Overall, with current tools and techniques, reported non-surgical retrieval success is high. One study found a 79.5% success rate using a microscope and ultrasonics (4). Ultrasonic methods alone have ranged from 33% up to nearly 100% success in different reports (4). The key is a careful, stepwise approach combining magnification, irrigation, mechanical loosening, and appropriate instruments.

Summary and Best Practices

Broken endodontic files are a known occupational hazard. Prevention (glide-path management, balanced forces, single-use files, avoiding excessive torque) remains the first line of defense. When separations occur, the endodontist must choose between bypassing, retrieving, or bypass-and-obturating. Evidence shows that a retained fragment does not automatically doom treatment as long as the canal is disinfected (3). Modern retrieval methods – especially microsurgical techniques (ultrasonic tips under a microscope, Masserann or loop systems, and adhesive micro-tubes) – make removal possible in the majority of cases (4). Ultimately, the strategy should balance microbial control with conservation of tooth structure. By understanding the causes of rotary file fracture and employing evidence-based management, endodontists can handle a broken file with confidence and maintain high success rates in endodontic file therapy.

References

(1) AAE Guidelines: American Association of Endodontists. “Treatment Options for the Retreatment of Nonhealing Root Canal Therapy.” https://www.aae.org/specialty/clinical-resources/treatment-options/

(2) Style Italiano Endodontics. “How to Retrieve a Broken File with DOM + Ultrasonics.” https://endodontics.styleitaliano.org/broken-file-retrieval/

(3) Madarati AA. “Frequency, causes, and management of endodontic mishaps.” Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40(4):301-316. https://rde.ac/DOI/10.5395/rde.2015.40.4.301

(4) Hulsmann M, Schinkel I. “Influence of several factors on the success or failure of removal of fractured instruments from the root canal.” J Endod. 1999;25(8):598-600. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10530265/